Work, Loss, and the Search for Purpose: A Christian Perspective on Netflix Hit, Train Dreams

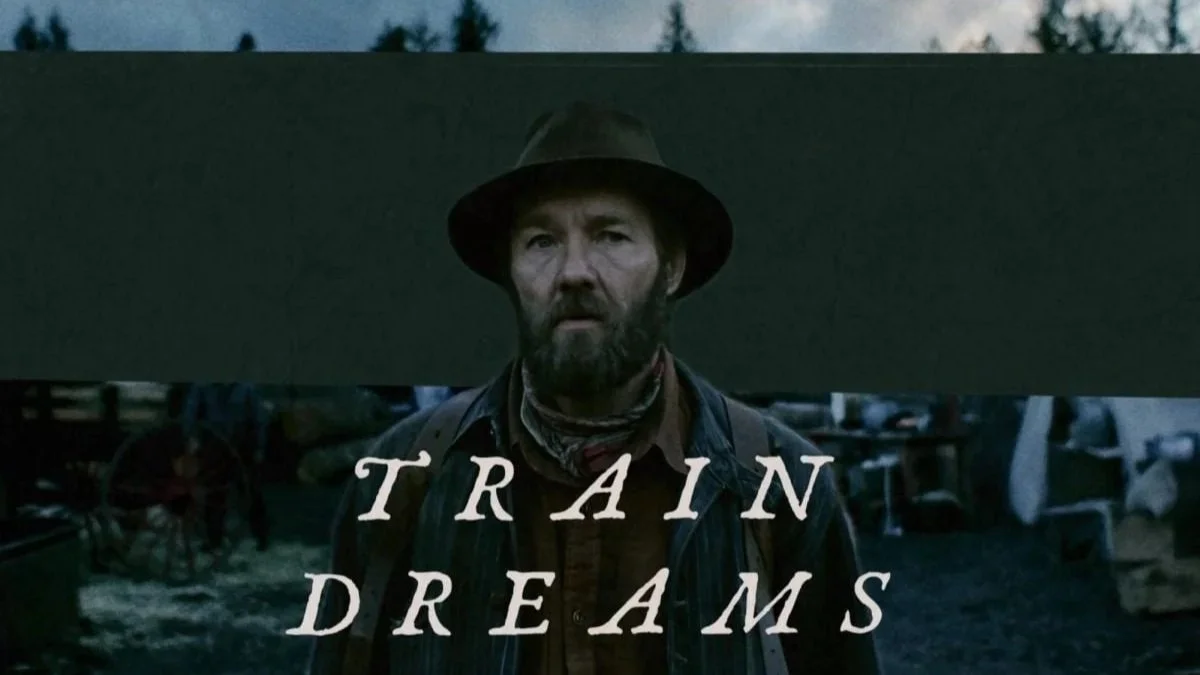

Joel Edgerton appears as Robert Grainier in Train Dreams, now streaming on Netflix.

This novella was recommended to me by my friend, Dr. Matt Castro. It’s a quick read—around 120 pages—but it carries the weight of a much longer life. Denis Johnson tells the story of Robert Grainier, a man shaped by loneliness, labor, and loss in the American West near the turn of the twentieth century. Without spoiling the plot, Robert’s life is marked by repeated catastrophe, interrupted by only brief pockets of ordinary joy. He is resilient—stalwart, loyal, and hardy—and yet the tone of the story is unmistakably melancholic: a man doing his best to live well while the world moves on without noticing.

One scene in particular captured that melancholy for me. Late in life, Robert rides a train across a wooden bridge he helped build years earlier. The bridge had been a monumental achievement, demanding months away from his young family and representing, perhaps, his most tangible contribution to a society that rarely stops to thank its builders. But as he crosses, he sees downstream a newer bridge—concrete and steel—built for cars. The moment lands with emotional force: his life’s work has been replaced without ceremony, rendered obsolete almost instantly. Robert absorbs the sting quietly. He keeps going. Yet the ache of insignificance—and the self-doubt that follows—stays close.

The story stirred several questions in me about purpose, suffering, and human flourishing. Robert survives much of what life throws at him, but his isolation is impossible to ignore. Loneliness seeps into nearly every page. (And because I hope you’ll read the book yourself, I’m intentionally leaving out major plot points.)

What is my purpose in this world?

As a Christian, I’m not left guessing. I believe I exist to glorify God and enjoy Him forever. God does not need my praise, prayers, or obedience to complete Himself—yet I desperately need His grace, mercy, and authority. By responding to His call in faith and repentance, I magnify His glory, and He displays His mercy in preserving and shaping me.

But what about those who live without God—either denying Him outright or treating Him as distant and uninvolved? That posture inevitably pulls life inward. Purpose becomes self-referential: my happiness, my success, my legacy, my people. That may work for a season, especially for someone surrounded by friends and family, but it becomes painfully thin in the face of loss—particularly for the lonely, the overlooked, or the forgotten.

Here I’m reminded of Philippians 4:7, which speaks of “the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding.” The biblical vision of peace is larger than calm feelings; it is closer to the Hebrew idea of shalom: wholeness, stability, flourishing—a life held together under God.

Without a defined purpose anchored beyond the self, life eventually begins to feel meaningless. Illness comes. Friends betray. Loved ones die. Children suffer. Work fades. Accomplishments are replaced. If the things we live for cannot last, what does it all mean?

In reality, we all worship something. If it is not God, it will be sex, money, power, approval, comfort, politics, friendships, or even our children’s achievements. Yet these “gods” are fragile. They do not love us eternally. They can be taken away overnight. Our desires can shift on a whim. Only the living God is unchanging, omnipresent, and faithful—loving us more deeply than we can love ourselves. Trust in Him gives a person reason to wake up, endure, and persevere. If God created us intentionally, then the center of life must be Him—and our purpose is to magnify His glory in everything we do.

How does a person deal with tragedy—especially tragedy beyond control?

Robert experiences his share of suffering, and it raises a second question: how do we live when hardship arrives uninvited? One person’s tragedy may be another person’s inconvenience, and our response to pain is often shaped by what we’ve known and what we expect from life. I’ve seen heartbreaking living conditions in places like India and China—and I’ve also seen genuine joy there. It’s disorienting to return home and watch people rage online over minor inconveniences: an air conditioner that’s not cold enough, a job that demands too much, a schedule that feels unfair. Perspective matters.

Still, I don’t mean to downplay real grief. Suffering is suffering. The question is what we do with it.

Robert—nominally faithful at best—seems to internalize pain by retreating. His solitude becomes his coping mechanism, but it also becomes a cage. In real life, others react differently: some become angry crusaders, some collapse into self-pity, some spiral into instability that burdens everyone around them. The strategies vary, but none are sufficient on their own.

My conclusion is simple, though not simplistic: the only stable answer is absolute trust in the goodness and authority of God—an authority we may not fully understand, but a God we can fully love. Scripture is filled with men and women who suffered far more than most of us will ever face and yet remained steadfast: Job, crushed under losses he could not explain; Joseph, betrayed by his own brothers and sold into slavery; Paul, faithful through repeated unjust imprisonments. Their peace was not denial; it was anchored hope. They were held by a God who rules even when life feels chaotic.

What does Robert’s loneliness reveal about the need for community?

Finally, Robert’s long solitude pressed on a truth I too easily minimize: human beings were not made to endure life alone. As a cheerful and dignified introvert, I can convince myself that my nuclear family is enough, and that relationships beyond it are optional. Scripture does not allow that conclusion.

The Christian life is a shared life. Hebrews 10:24–25 calls believers to stir one another up to love and good works and to refuse the habit of isolation. Acts 2:42–47 describes the early church eating together, praying together, and sharing resources for the common good. (This is not an endorsement of governmental communism; the difference is crucial: their generosity sprang from shared faith and love, not coercion.) And throughout the New Testament, God advances His kingdom through a body, many members, different gifts, shared mission. Scripture never presents the heroic lone Christian as the model of spiritual health.

Isolation may feel manageable in the short term, but over time it denies the kind of flourishing God intends. We are commanded to sing together, serve together, give together, confess together, and sit together under the Word. Community is not a luxury for the strong; it is a means of grace for the weak—which is to say, for all of us.

Closing thought

There is also a film adaptation of Train Dreams on Netflix, and I thought it was well done. Some characters are changed and the timeline is rearranged, but the message remains: life is fragile, work is forgotten, and loneliness is costly. I enjoyed the film, though my wife—beautiful, adoring, and theologically sharp—summed it up in one word: “depressing.”

I think she understood the point.